© 2020 Ken Quattro

One of the first questions I am usually asked regarding INVISIBLE MEN is: Why did you write it? My answer is clear and succinct: Mr. Samuel Joyner.

Mr. Joyner was a Black cartoonist from Philadelphia and the man who started me on my long inquiry into the history of Black comic books artists that resulted in my book, INVISIBLE MEN. We first corresponded nearly 20 years ago when I contacted Mr. Joyner regarding information about Matt Baker. He kindly responded not only with information about Baker (whom he met only once), but a host of other Black artists.

His response started me on my quest that lasted over 15 years, to document the lives and careers of the first generation of Black artists and writers to work in the comic book industry. Mr. Joyner was a link to a forgotten past. He and future comic book artist Cal Massey were young friends in the late 1940s when they made the trek to New York City together to meet other Black commercial artists and get tips on how to enter the industry themselves .

As with all the artists who appear in INVISIBLE MEN, Mr. Joyner also had an interesting life story. And like all the others, his story really began before he was born.

_____________________________________________

Like many Blacks headed north during the Great Migration in the early years of the 20th Century, Samuel Joyner settled in the first major city he came to north of the Mason-Dixon Line: Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

While his father worked in Norfolk, Virginia shipyard, Samuel went in another direction. Whether he started his trade in his hometown of Portsmouth or learned it when he got to Philadelphia is not known. What is known is that in 1909, Samuel started up his own business as a house painter and paperhanger.

“…from the middle class to rural women to the working-class immigrant; all women, regardless of their class status, income, or geographic location were believed to be susceptible to the sensuous qualities of wallpaper. Like many other consumer goods, wallpaper’s affordability and availability helped to democratize the American interior and to blur the apparent boundaries of social class.” [Jennings, Jan. “Controlling Passion: The Turn-of-the-Century Wallpaper Dilemma.” Winterthur Portfolio, vol. 31, no. 4, 1996, pg. 254.]

Appealing to all who desired professional home improvements, Samuel ran advertisements in both the large white-owned PHILADELPHIA INQUIRER and the Black-owned PHILADELPHIA TRIBUNE.

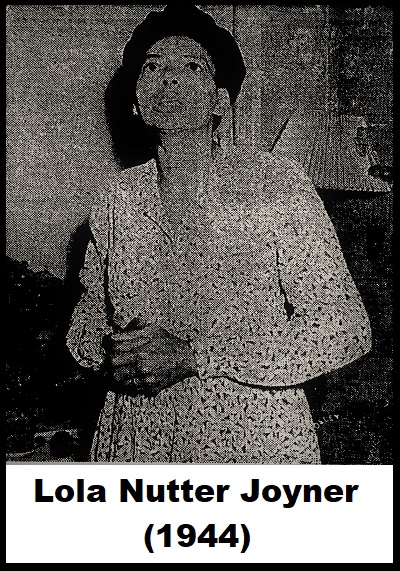

Samuel established his business and eventually met and married a young woman who had moved to the city from Nanticoke, Maryland. Lola Elizabeth Nutter.

Lola’s father was an oysterman; one of the many Blacks toiling in the lucrative industry that flourished in Chesapeake Bay.

“Since the Chesapeake Bay was, by 1860, the main supplier of oysters in the United States, oystering was a natural pursuit for blacks, as it was for others. With little capital outlay required and a high demand for seafood, which had begun to boom in the late nineteenth century, individuals could make a modest living alongside larger companies that were operating for much bigger stakes.”

“‘Oystering was one of the highest paying jobs for black men…'” [Anderson, Harold, “Slavery, Freedom and the Chesapeake,” MARINE NOTES, pps. 4-5, March-April 1998.]

Lola grew up surrounded by a large extended family unit, consisting of the Nutters and the Elseys, that expanded when her parents divorced when she was very young and her father remarried. It was a period of her life that she later recalled fondly.

“When I was a little girl, I wrote jingles and Mrs. Beckett’s mother, the late Mrs. Elsey, who was my teacher, kept them in a little book for me.” [Prigmore, Barbara S., “Mother of Three In Great Demand As Poet-Reader,” PHILADELPHIA TRIBUNE, Aug. 19, 1944.]

Upon coming to Philadelphia, Lola became a cook in a white household. She would continue to work as a “domestic” for a while even after she and Samuel married. Once her children were born–four boys in six years–Lola relinquished her outside job and stayed home to raise them. Samuel, meanwhile, continued to work steadily, even during the Great Depression, maintaining his business and even serving as the president of the local Paper Hangers and Painters’ Mutual Association.

Lola actively encouraged her children to explore their talents. The formation of the Works Progress Administration (WPA) by the federal government in 1935, created opportunities for minorities in the arts. One WPA community outreach program offered art classes to interested children and then sponsored an exhibition of their work at a local settlement house. Among the exhibitors were several of Lola’s boys, including her oldest, Samuel Hudlen Joyner, Jr. Misidentified as “Daniel” in the article accompanying the photograph, Samuel was selected for special mention.

“[Samuel] Joyner had his pastel of a landscape in the recently concluded Cultural Olympics which reached the final rounds.” [WPA Youngsters Amaze Proud Parents,” PHILADELPHIA TRIBUNE, July 8, 1937.]

There was no such mistaken identification in a later article which also mentioned his participation in the Cultural Olympics and noted Samuel’s future ambitions.

“Samuel plans to enter the field of commercial art, a good choice, since there is much opportunity in it for Negro boys and girls.” [Butler, Anne, “Presenting,” PHILADELPHIA TRIBUNE, Feb. 10, 1938.]

Samuel attended South Philadelphia High School which provided him with an education in both art and entrenched discrimination.

“Art teachers began to notice his flare for color schemes and his attention to detail. The would comment on how ‘unusual’ it was for a ‘colored boy’ to be such a good artist. Yet, while his white instructors were constantly praising and applauding him, they were also constantly discouraging him from pursuing a career in commercial art. They would give him the ever-stereotypical line that a ‘Negro shouldn’t waste time on all them silly dreams of drawing because no white man is ever going to pay a single dime for those damn doodlings. Stick to something you can make money with…like a trade.'”

“The ‘money-making’ career choice they tried to force him to pursue was landscaping.” [Rochon, Michael J., “Legendary Cartoonist Leads By The Pen,” PHILADELPHIA TRIBUNE, March 27, 1998.]

Undaunted, the budding artist transferred out of South Philadelphia High to the Edward Bok Vocational School to further his studies in his chosen career.

The future may have looked bright for Samuel, but not so for his younger brother William. William, who shared his older brother’s artistic skills, had an unidentified, but lingering illness. The details of it not made public, but its ravages were crippling and costly.

“Friends of William Joyner, 17 year-old son of Mrs. Lola Joyner of 1816 Webster street [sic], are giving a musicale on Friday evening, October 30, at Tindley Temple to raise fund to buy him an artificial leg.” [“Glances,” PHILADELPHIA TRIBUNE, Oct. 24, 1942.]

The well-meaning efforts of the community would matter little, as on November 5, 1943, William Joyner, just 26 days past his 18th birthday, died of lung cancer.

The death of one so young, the death of a sibling, must have been devastating for Samuel. In the wake of his brother’s death, Samuel (who was working in his father’s company as a painter and paperhanger) enlisted in U.S. Army on January 12, 1944, several weeks before he would turn 20 years old on February 7.

As can be imagined, William’s death also effected his mother deeply. During his illness she found comfort in her church, Tindley Temple and for solace, she turned to writing and reciting, inspirational religious poetry.

“Altho [sic] Mrs. Joyner has had no special training in composing poetry her poems are realistic, rhythmical and have great religious emotional appeal”

“It was her son, Samuel Jr., now in the armed forces stationed at Rome, Georgia, who encouraged Mrs. Joyner to write poetry.”

“‘My son, Samuel, said to me just before he left for camp, ‘Mother, continue to write those beautiful thoughts you have about people and things, then rewrite them. For it is real poetry.'” [Mother of Three, Prigmore.]

Samuel was serving at Camp Claiborne in Louisiana when he became too ill to continue his training. He was sent to Battey General Hospital in Georgia for treatment for a pre-existing condition. While there, according to his mother, he was assigned to be the “‘cartoonist for the Army’s daily paper, at the Special Service Branch.'” [Mother of Three, Prigmore.]

Samuel was discharged on August 22, 1944.

Lola continued giving recitations of her poetry at Tindley Temple and beyond. As her notoriety grew, she would receive “star” billing in advertisements promoting her poetry readings.

Sadly, tragedy would once again strike the Joyner family. Lola took ill in the early days of 1946 and on January 11, she passed away from pneumonia. She was only 52 years old.

A few months later, honoring a wish Lola had expressed in the TRIBUNE article in 1944, Samuel paid for the publication of THE POEMS OF LOLA NUTTER JOYNER, a 44-page collection of her poetry.

Despite the personal tragedies, Samuel continued toward his goal of becoming a commercial artist. He enrolled in classes at the Philadelphia Museum of Art School in 1947. Coincidentally, that put him in the same school at the same time as several of the Black artists and writers who would help create Orrin C. Evans’ ALL-NEGRO COMICS #1. If Joyner ever knew about the planned publication or if he was ever approached about working on it, is unknown.

Soon after, Samuel and another aspiring commercial artist named Cal Massey would make the trip north to New York City to visit with working Black professionals and to check out the prospects in the field.

“Around 1950 or 1951, [Massey and] I went to New York City with my portfolio of cartoons and advertising spot drawings. As a beginning cartoonist I was encouraged to talk to other colored illustrators for information about breaking into the lucrative field.”

“I was given the names and studio address of a few African-American professionals. Most worked in Manhattan. E.C. Stoner, Matt Baker, Ted Shearer, Chas. Allen, Mel Bolden…etc.”

“Most of these illustrators were earning lots of cash, but they took time from their busy schedules to offer me encouragement. I’m sorry I didn’t take my camera.”

“I visited Matt Baker’s studio workshop only once and he too was encouraging. I was with another beginner [Massey] and Matt showed us several pages of comic book art, gave us tips on how to approach assignments. The other artist and myself were thrilled to meet and talk to Matt Baker. Sorry that my encounter [with him] was so limited.” [Joyner, Samuel. Letter to the Author. 4 April, 2004.]

As detailed in INVISIBLE MEN, Massey would go on to work steadily in comic books during the 1950s. It was through him that Samuel would make his own, brief foray into the industry.

“Calvin Massey and I worked in the same downtown art/illustration studio in the 1950s. When Cal was struggling to meet deadlines on some of his comic book pages, he would slip me a few greenbacks to ink in some of the comic book backgrounds and balloon lettering.” [Joyner, Samuel. Letter to the Author. undated.]

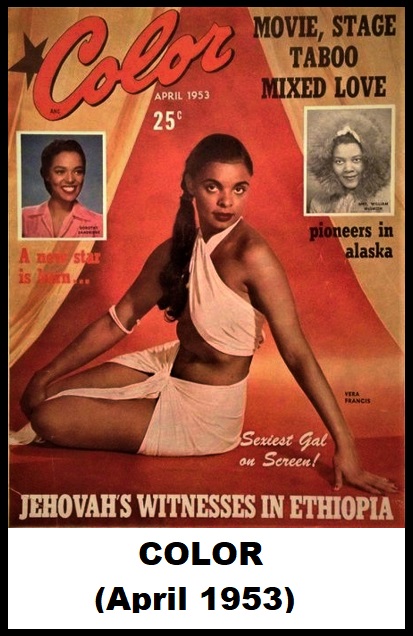

Around the same time, Samuel became the art director of Ira J. K. Wells’ COLOR magazine. This was the first pictorial magazine aimed at the Black readership, predating EBONY by a year. Samuel worked for COLOR for six years, his tenure ending when the magazine folded in the mid-1950s.

In the summer of 1953, Samuel married Grace Hutty.

Grace was a graduate of West Philadelphia High School and four years older than Samuel. She was working at RCA in Camden, New Jersey as an electronic technician when she and Samuel married.

Meanwhile, despite the obstacles, Samuel established himself as a Black commercial artist working in a predominantly white field.

“The commercial [art] companies appreciated his art, but in every instance, there was a catch. All of his characters had to be white people, no ‘colored,’ no exceptions.”

“‘All of my characters were of blond and blue-eyed white people,’ Joyner recollects. ‘I did my best to make them look extra-white, all Scandinavian. You see, the white establishment would not allow colored art work. The didn’t want it or recognize it.'”

“Joyner also remembers how the agencies would send out the representatives to sell his work under the presumption he was white.” [Legendary Cartoonist, Rochon.]

Samuel elaborated in a personal letter, reiterating experiences told by other Black artists in INVISIBLE MEN.

“A white art salesman sold my drawings because some clients did not want me to come to their offices during the 1950s.” [Letter to the Author, Joyner.]

Despite the blatant prejudice and discrimination he was subjected to in the field of advertising, Samuel persisted.

“I drew a multitude of stylized illustrations with Caucasian characters for clients like General Electric, Sears Roebuck, Lukens Steel Words, etc., etc. I was not allowed to sign my name to the art, but the pay was very good.” [Letter to the Author, Joyner.]

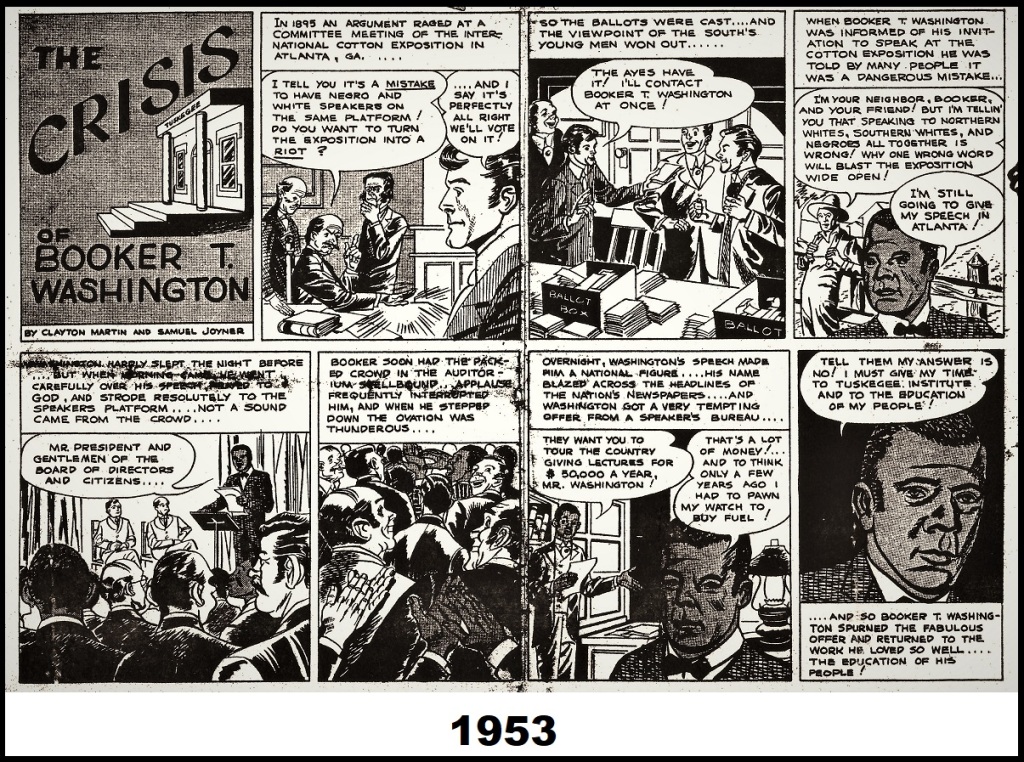

As he was trying to break through into the white world of commercial art, Samuel never left the Black media behind. He continued drawing for both local and national Black newspapers. One example came in the form of the comic strip “The Crisis of Booker T. Washington” he co-created with writer Clayton Martin in 1953.

Samuel opened up his own print shop in the 1960s, returned to school and earned his teaching certificate by taking evening classes at Temple University. This allowed him in 1974, to begin teaching art and visual communication classes at Edward Bok Vocational School, his alma mater.

Samuel continued teaching at Bok until 1990, all the while providing spot illustrations, advertisements and cartoons for various publications.

On July 27, 1994, tragedy once again touched Samuel’s life when his wife, Grace Hutty Joyner died.

Now a widower, Samuel carried on. He still found steady work in the Black newspapers, often illustrating political cartoons or historical panels depicting Black history.

In 1996, the National Newspaper Publishers Association (NNPA), a group representing 205 Black-owned newspapers, awarded Samuel the first place award for having drawn the best editorial cartoon that year.

Over time, he became an inspiration to younger generations of Black artists and cartoonists. He was a recurring guest at the annual East Coast Black Age of Comics Convention (ECBACC) in Philadelphia and his collection of original artwork formed the “Exhibitions of Samuel Joyner: A Cartoonist” at the Urban Archives at Temple University in 2002. Eventually, Samuel donated his collection of art, photographs and related ephemera to Temple forming the Samuel Joyner Art Collection.

And even as he reached his ninth decade of life, Samuel H. Joyner Jr. never stopped drawing.

_____________________________________________

One last personal note.

In his final letter to me, in 2006, Mr. Joyner made mention of the book I told him I was working on regarding the Black comic book artists.

“If I am still around, Lord willing, when you finish your book, please mail me a copy.”

That line haunts me. Mr. Joyner passed away at the age of 96 years old on March 24, 2020. Eight months before INVISIBLE MEN was released.

I will always remember Mr. Joyner’s kindness and grace. He was truly a wonderful human being and the reason this book exists.